After reading a fellow blogger’s heartfelt post about last week’s suicide of our mutual friend and colleague Alex Meservey, specifically her plea to those who are struggling: “when [you] feel alone, the truth is the opposite,” I decided to write about my feelings on how we as a nation should be viewing depression and mental illness in general.

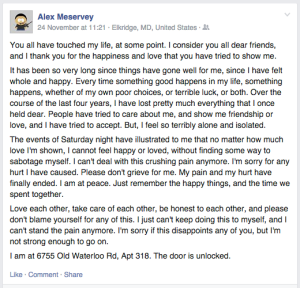

In order to illustrate my views, I must first start with the heart-wrenching note that Alex posted to facebook. When I woke that morning and saw this message, it was real-time. I watched a flurry of activity, his nearby friends calling the police, people generally freaking out. But eventually it was confirmed: he was already gone.

The most important line that I read in his message is, “People have tried to care about me, and show me friendship or love, and I have tried to accept. But, I feel so terribly alone and isolated.” In other words, despite recognizing love and camaraderie, he felt alone.

I am by no means suggesting that we can’t help. To the contrary, we must be in tune with how people are feeling and what issues they might be experiencing. We must be ready to refer them to professional assistance. We as friends, family, and colleagues, must ourselves understand that there are resources such as suicide crisis hotlines, including hotlines specifically dedicated to veterans like Alex–a former marine who even as a civilian continued to serve our country, often in undesirable overseas locations such as Iraq.

But just knowing the avenues and being there for someone, are not enough. If all that people needed was to know crisis hotline numbers or what resources were available, then suicide rates would be going down–not up. There is more information in schools, universities, and military circles today, than there was when I was growing up or during my three years in the Air Force. Lack of information and resources is not the problem.

We must, as a nation, accept mental illness as a medical illness. We must work to eliminate the stigma. People should feel comfortable asking for professional help. Parents must overcome the fear that they will be seen as failures if their children need assistance. Our society, as a whole, has a responsibility to protect its citizens. We need to work together to help those with mental illnesses before they do harm to themselves, or to others. We need to make this a health care priority not only when a tragedy makes headlines, but every day.

As CNN reported in November 2013, “Every day, 22 veterans take their own lives. That’s a suicide every 65 minutes. As shocking as the number is, it may actually be higher [because] the figure, released by the Department of Veterans Affairs in February, is based on the agency’s own data and numbers reported by 21 states from 1999 through 2011.” We have more states unreported than reported, and the unreported states include three of our five largest states. The article goes on to illustrate who else might not be counted in the statistics, and it’s too many. According to a Time Magazine article from January 2014, “The number of male veterans under the age of 30 who commit suicide jumped by 44 percent between 2009 and 2011, the most recent year for which data was available.”

In the National Institute of Mental Health’s pages defining mental illness, they give us this important information: “Depressive illnesses are disorders of the brain. Brain-imaging technologies, such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), have shown that the brains of people who have depression look different than those of people without depression.” That’s a medical condition, not someone having the blues or not being able to handle life because they’re weak.

A loved one of mine, I’ll call him Jim, struggles with depression. One night, Jim told us that his friend just couldn’t understand. Jim’s friend was not enjoying the same personal life as him–his friend perceived that his own parents were not as loving, and things just weren’t “as good.” But, Jim’s friend said, he didn’t understand: Why, when things were generally going fine in Jim’s life, was he depressed—while his friend’s circumstances felt less favorable in comparison, yet he was happy as a person.

No one really understands. Why can depression affect someone whose life seems good, but someone whose life doesn’t seem as good, is not depressed? There are internal factors. We have to accept that. We also have to accept that we don’t have to understand it, in order to help.

When I worked with Alex, we spent countless hours together; and yet I did not know he was not feeling life the same way I was. We TDY’ed together, including, say, spending two months as the only two English speakers living directly on site. You spend a lot of time together. You’re bored. You talk. But you don’t necessarily talk about feelings—especially with a former Marine who actually, physically, reminded people of Genghis Khan. Everyone who knew Alex described him as imposing, intimidating, and confident. He was complimented for his confidence when we worked together. What we perceived in Alex was confidence, but what Alex felt was not confidence. It was isolation.

As the National Alliance on Mental Illness notes, “Just as diabetes is a disorder of the pancreas, mental illnesses are medical conditions that often result in a diminished capacity for coping with the ordinary demands of life…Mental illnesses are not the result of personal weakness, lack of character or poor upbringing.”

And yet, we treat depression and mental illness as a weakness. Mental Health America notes that “Too many people resist treatment because they believe depression isn’t serious, that they can treat it themselves or that it is a personal weakness rather than a serious medical illness.”

We must overcome how mental illness is viewed, in order to treat mental illness in more people. We must work to remove the stigma. If you saw someone struggling in the water, you would either help them out or call a lifeguard. There are people who are struggling at life. We must not only call them a lifeguard, but teach them to swim.

I talked to Alex the day before this happened. I gave him shit like every Marine does. I was his friend and had no idea. I’m across the country. No excuse. I should have known.

Sometimes, there’s no way to know.

Thank you for this. Especially the emphasis on medical illness. There is still too much of a stigma.

I was once arguing with a Marine. (Clearly, I’m a glutton for trouble.) He loved to ride his motorcycle, but went without a helmet. I lectured to him: since he spent so much of his life for service and duty to his country, he owed it to himself to take care of himself. I don’t believe for a minute he ever put on a helmet after that, but I think my point hit something in him based on the way he reacted. Thank you for reminding me.. I will need to say that more often.

That definitely is a good way to put it!